Paper review: MapReduce

Recently, I started a study group to work through the famous MIT 6.824: Distributed Systems together with some friends. The course includes a number of readings that are closely related to the labs. Instead of simply skimming through the papers, this time I decide to write a review for each paper, similar to the morning paper style. Given this is an after work side-project, maybe I should call them the late night paper?

Anyway, without further ado, let’s jump into the first paper about MapReduce1.

What

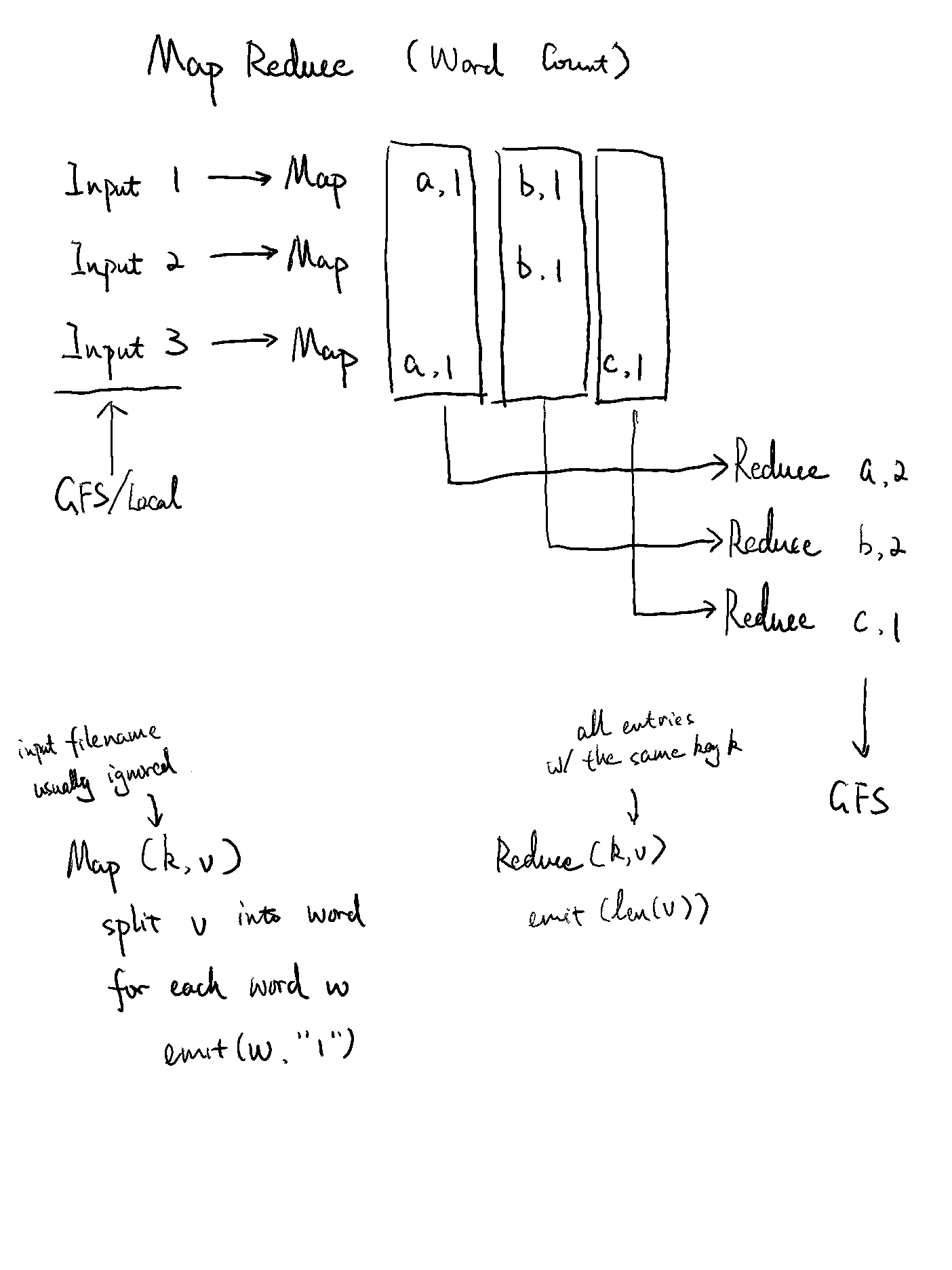

MapReduce is a programming model and an associated implementation for processing and generating large data sets. Users specify a map function that processes a key/value pair to generate a set of intermediate key/value pairs, and a reduce function that merges all intermediate values associated with the same intermediate key.

Why

To understand why Google needed it in the first place, the thing to focus here is the “large data sets”. Google needed to process multi-terabyte data-sets that couldn’t be handled with a single computer (remember this paper was published back in 2004, and it’s still not easy in 2022). As a result, the date is split into smaller pieces and distributed among 1000+ machines, which are just commodity PCs. While a single commodity PC is quite reliable, once you have thousands on them running together, there is always something broken.

Before MapReduce, a programmer has to manually implement a distributed system that can handle data distribution (i.e. splitting the input data), parallelization (i.e. organizing 1000+ machines), load balancing (i.e. ensuring no machine is overloaded), and fault tolerance (i.e. handling the unavoidable failures from machines). You can easily see how this model won’t scale: every programmer has to be a distributed system engineer to get any work done. The answer Google came up was MapReduce.

How

MapReduce includes two parts: a simple programming interface Map and Reduce for programmers to model their problems, and an implementation of the run-time system that hides the messy details of engineering a distributed system.

Interface

Map, written by the user, takes an input pair and produces a set of intermediate key/value pairs. The MapReduce library groups together all intermediate values associated with the same intermediate key I and passes them to the Reduce function.

The Reduce function, also written by the user, accepts an intermediate key I and a set of values for that key. It merges together these values to form a possibly smaller set of values.

The interface closely resembles the map and reduce primitives in functional programming languages. Traditionally in functional programming, Map operates on a list of values and produces a new list of values, by applying the same computation to each value. Reduce operates on a list of values and collapses those values into a single value (or some number of values), by applying the same computation to each value. Both are higher-order functions that you can combine them with your own functions to tackle your problem domain.

In MapReduce the interface resolves more about the key/value pair notion. The key makes the partition and grouping work easier in the implementation.

This interface is expressive enough for many problems that Google programers need to solve, and the most significant one is the indexing for the Google web search service (note that it has moved away from MapReduce in recent years). But there are limitations to this programming model.

- No iteration or multi-stage pipeline: you may need more than one MapReduce job to solve your business problem. In fact, quoted from the paper “the indexing process runs as a sequence of five to ten MapReduce operations”. A programer still need to creatively break down a problem into several MapReduce jobs and glue the results(I imagine it’s a combination of scripting and leveraging GFS to share intermediate output files).

- No real-time/streaming processing: MapReduce is effectively a batch processing model, where you need to know all your input before start. In recent years, the industry seems to move toward the streaming model where the system can work with partial/incomplete data incrementally.

- The only way to share states is via intermediate outputs: Google has GFS that mostly solves this problem, but there is just not a lot of flexibility.

Run-time system

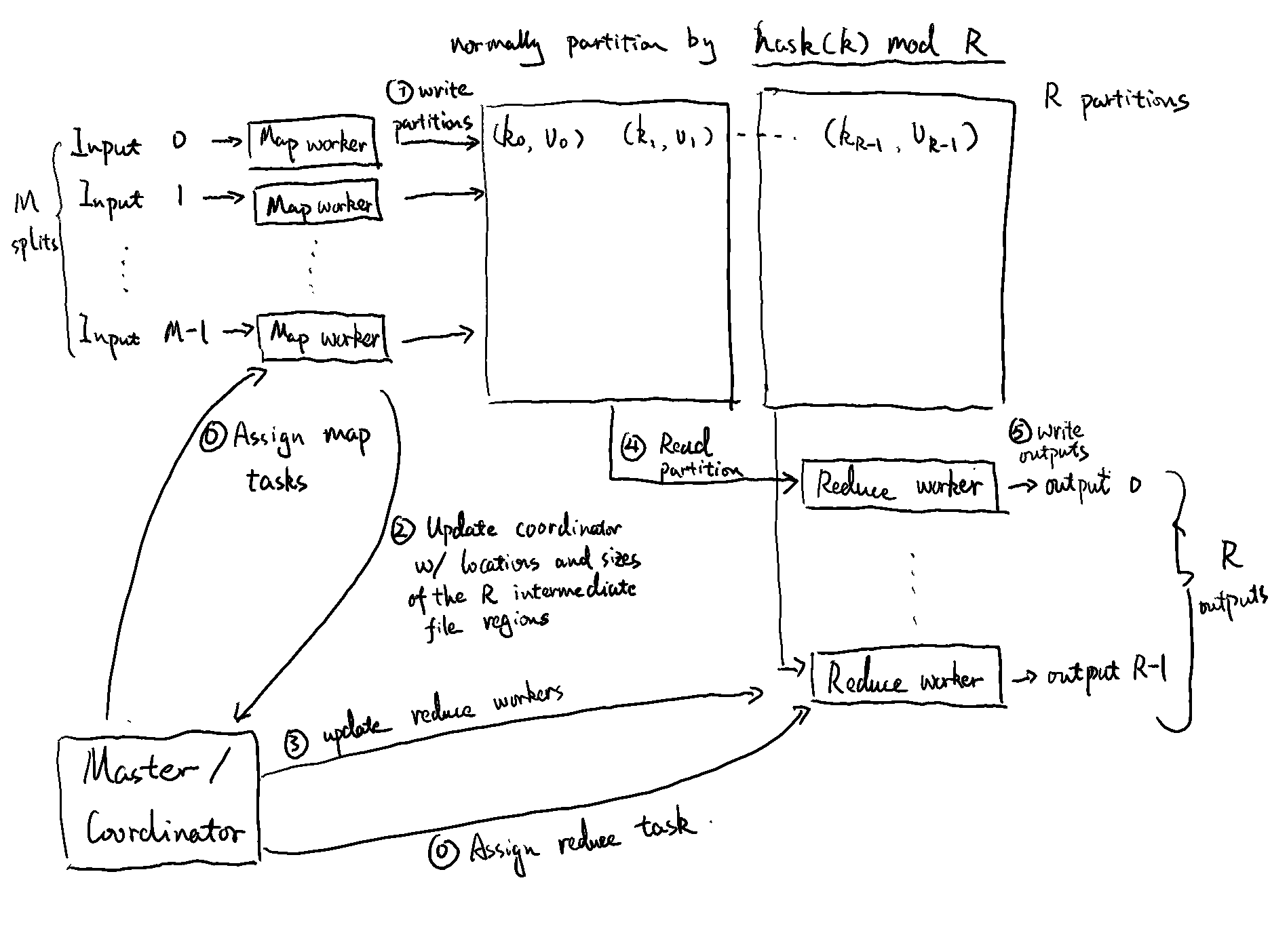

Hidden under the simple map/reduce interface is the run-time system that handles the messy details of a distributed system. Conceptually, there are three types of roles in a MapReduce system

- A set of M map tasks,

- a set of R reduce tasks, and

- a “master” (as it’s called in the original paper) or “coordinator” (as it’s called in the assignment) task that coordinate the interactions between map and reduce tasks.

Their interactions can be roughly described as below.

Workers

Both the map and reduce workers are relatively “dumb”: they mostly just read data from a given location in a network file system, run a pre-defined function on the data, writes the output back to the network file system, and notify the coordinator when they are done. They don’t know the existence of their peer workers, they don’t have a back channel to share any information with their peers, and they only work on their own small piece of data. The “dumb” workers enable the horizontal scaling, because you can divide and conquer the big problem into small enough pieces that one worker can solve, and in theory you can throw in as many workers as possible to scale out infinitely.

Master/Coordinator

The coordinator is where the “smart” operations happen. Its primary role is to support all map and reduce workers to tackle the problem together:

- It picks up idle workers and assign each one a map task or a reduce task.

- It receives the completion updates from map workers, and forward them to reduce workers as the middleman.

- It wakes up the user program when the whole job is completed.

To get its job done, the coordinator has a couple of bookkeeping responsibility:

- It needs to store the state, which can be one of idle, in-progress or completed, for each map task and reduce task.

- It needs to track the identity of the worker machine for non-idle tasks (i.e. in-progress and completed).

- It needs to store the locations and sizes of the R intermediate file regions for each completed map task, and push incrementally to workers that have in-progress reduce tasks.

With essentially the states of all workers and tasks at hand, the coordinator has the opportunity to further facilitate the operation.

It health-checks every worker. If a worker does not respond in a certain amount of time, the coordinator marks it as failed, and reset the states of the corresponding tasks with the following rules

- Any map tasks completed are reset back to their initial idle state and become eligible for rescheduling. This is because their output is stored on the local disk of the failed worker.

- Any map or reduce task in progress is reset back to idle and become eligible for rescheduling.

When a MapReduce operation is close to completion, the coordinator also schedules backup executions of the remaining in-progress tasks. The idea is to avoid “straggler” tasks due to bad hosts.

Another smart thing that the coordinator did is to schedule a map task as close as possible to its input data. This is to address the network bandwidth issue that happened in data centers back in 2004. Back then, computers are connected to switches in a tree-like topology. Therefore, the “root” switch which has limited bandwidth becomes the bottleneck. However, this is no longer an issue in a modern data center, where a computer is connected to multiple switches.

Given its importance, you might think the MapReduce system provides fault tolerance to the coordinator. But turns out it doesn’t.

It is easy to make the master write periodic checkpoints of the master data structures described above… However, given that there is only a single master, its failure is unlikely; therefore our current implementation aborts the MapReduce computation if the master fails.

I appreciate their pragmatic approach here a lot. It’s tempting to implement a “perfect” fault-tolerant system, and it’s not that hard to support fault tolerant to the coordinator. But the probability of this happens is so low that the gain is extremely marginal. It’s best to just keep the system simple.

Dean, Jeffrey, and Sanjay Ghemawat. 2008. “MapReduce: Simplified Data Processing on Large Clusters.” Communications of the ACM 51 (1): 107–13. https://doi.org/10.1145/1327452.1327492. ↩︎

Published on: Last modified: